Jean Jaurès is not well-known or much-translated in English. The hero of turn-of-the-20th-century French socialism was revered across the international left following his assassination in 1914. He was dining with friends when a nationalist shot him dead. A few days later, Anatole France wept in the pages of l’Humanité:

My overflowing heart explodes. I can only stammer. My pain suffocates me. To never see him again, he who had the biggest of hearts, the most vast of geniuses, the most noble of characters.[1]

Bordiga compared Jaurès to Christ[2]. Trotsky called him “the prototype of the superior man who must be born of suffering and setbacks, of hope and struggle.”[3] Blum argued that “His person, his work, his name embodied socialism, international socialism, revolutionary socialism.”[4] Zinoviev announced that “The Russian workers have raised in their red capital of Moscow a monument this last year to Jaurès […] venerated by all the conscious workers of the world.”[5] In 1923, Germaine Berton assassinated far-right leader Marius Plateau, attempting to avenge Jaurès. During her trial she turned to another reactionary, Léon Daudet, and said:

I wanted to kill you because you are responsible for the assassination of Jaurès. I am an anarchist, but that does not prevent me from venerating Jaurès. My grandfather, an old socialist, took me to meetings where I heard him speak […] I deeply regret killing Marius Plateau instead of you.[6]

She was acquitted. In 1924, Jaurès’ remains were enshrined in the Panthéon alongside Rousseau, Hugo, and Zola. Why was this man loved by everyone from social democrats to individualist anarchists, and what can we learn from him?

A Reluctant Revolutionary

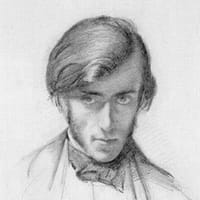

Jean Jaurès was born in 1853 to a humble Occitan family at Castres, in the verdant Tarn lowlands north of the Black Mountain. He was a good student and his father hoped he would become a postmaster, but a visiting school inspector recognized the boy’s precocious intellect and helped him get a scholarship. Jaurès would go on to France’s highest university and study philosophy, writing two doctoral theses: the first on the intellectual origins of German socialism, the second on the metaphysics of the sensible world, which he dedicated to his benefactor.

Jaurès’ began his political life as a republican, and reluctantly. He was convinced by local activists to stand for election and oppose the rise of the far-right. His uncle was something of a war hero, and as a well-spoken member of the faculty, Jean agreed to be useful—although he would have preferred to focus on philosophy. When he lost his seat after his first term, he was content to return to academic life. Anatole France in the same letter cited above recalls finding Jaurès in his “poor but glorious” house reading Euripides in the original Greek: Jaurès was an intellectual who accepted to become a man of action. By the time he finished his doctorate, he was a confirmed socialist. He came to the aid of the embattled miners and glassworkers of Carmaux in their bloody strikes, and was elected their representative in the face of armed repression. In the National Assembly, he called for the social emancipation of the proletariat:

It is because socialism is the only movement capable of resolving this fundamental contradiction of contemporary society, because socialism proclaims that the political Republic must lead to the social Republic, because it wants the Republic to be asserted in the workshop as it is asserted here, because it wants the Nation to be sovereign in the economic order and break the privileges of idle capitalism, as it is sovereign in the political order, that socialism emerges from the republican movement. It is the Republic that’s the great leader: bring her before your gendarmes![7]

Jaurès was not only a tribune of the plebs. He encouraged the first workers’ cooperatives developing across the south of France. He began the influential and Marxist History of the French Revolution. He was a journalist, lecturer, and dogged parliamentarian. And he took up the cause of captain Dreyfus.

A Militant Humanist

The Dreyfus Affair was a decades-long antisemitic political conspiracy that pinned treason on an innocent man. Dreyfus languished in the “dry guillotine” of Devil’s Island for years while Zola, Jaurès, and his other supporters campaigned for justice. Dreyfus would be fully exonerated in 1906, and in 1908 a far-right gunman failed to assassinate him. Jaurès responded to criticism from both opponents and allies of the socialist cause regarding the defense of Alfred Dreyfus in his article, “The Socialist Interest”. Addressing accusations of hypocrisy for being “worried about legality” while promoting revolution, he argued that bourgeois law has two components: laws enshrining capitalist power and laws affirming hard-won human rights. For Jaurès, revolutionary socialists aim to abolish the laws of exploitation and uphold the laws of justice.

Jaurès rebuked those who dismissed Dreyfus as a privileged bourgeois. Jaurès argued that Dreyfus’ wrongful conviction and extreme suffering transcended class distinctions, reducing him to human misery incarnate—a living symbol of injustice. Dreyfus embodied the failures of military authority, political cowardice, and systemic corruption, making him a figure of revolutionary significance. His case exposed the inherent violence and falsehood of the bourgeois social order.

Jaurès argued that the proletariat had a direct stake in addressing the injustices revealed by the Dreyfus Affair: if unchecked, the arbitrary power of the military, its glorified repression, and the normalization of court-martial chicanery would inevitably harm the working class. Exposing and opposing these abuses was therefore critical to defending the workers’ movement and undermining reactionary forces. Jaurès defended Dreyfus because he stood in solidarity with him as an individual man, upheld human rights for all, and believed it was in the best interest of the workers to do so.

Jaurès was killed because his leadership, politics, and courage posed too great a threat to the powers of this world: and it is for these very same qualities that his memory is cherished by all friends of freedom. His stalwart opposition to the insanity of the coming World War signed his death sentence. As with Dreyfus, many socialists either opposed Jaurès or would break with him over support for the war. The most notable example is Jules Guesde, who on both counts parted ways with Jaurès: and it is not by accident that Lenin would associate the Bolsheviks with Guesde and Jaurès with the Socialist Revolutionaries and Mensheviks.[8]

An Inconvenient Memory

Now we have come to the problem of Jaurès’ legacy: although the likes of Lenin disagreed with him vehemently, they could not excise him from the hearts of the workers. Jaurès was not merely a French leader, but a major figure of the Second International. He was fluent in German and spoke to German workers in their native tongue. He was so beloved in Italy that children were named after him.[9] This global fame and universal love was problematic for the Bolsheviks, because in substance they disagreed with Jaurès on critical issues but did not want to cede the memory of Jaurès to their opponents. We can see the conflict clearly in the words of Trotsky:

In France, before the war, there were two tendencies in the socialist party [...] There was a great struggle between Jaurès and Guesde, and in that struggle, it was Guesde who was right against Jaurès. We can never forget that.

When we are told that we are separating ourselves from the Jaurèsian tradition, this does not mean that we are entrusting the personality of Jaurès and his memory to the dirty hands of dissidents and reformists. It only means that there's been a great change in our politics, and that we'll fight against the survival and biases of the so-called Jaurèsian tradition in the French labor movement.

It is a disservice to the working class in France to have turned this incident into a conflict of ideas, as if the Communists could really claim to be part of the democratic and socialist traditions of Jaurès.[10]

And what, according to Trotsky, is the ideological content of Jaurès “democratic and socialist traditions”?

For the democrat Jaurès, socialism was the only way to consolidate and complete the Republic. […] In his indefatigable hope for an idealist synthesis, Jaurès began as a democrat ready to adopt socialism and became a socialist who took responsibility for full democracy. […] in his eyes, the proletariat was a historical force in the service of right, freedom, and humanity. […] In politics, Jaurès combined an extreme acuity of idealist abstraction with a strong intuition of reality. This was evident in all his work. The material idea of Justice, of the Good, went hand-in-hand with an empirical appreciation of even minor details. Jaurès understood men and circumstance perfectly, and knew how to make the most of both.[11]

As the historian Guillemin highlights, Jaurès refers obliquely in his work The New Army to his “inner thought, which in this world so cruelly ambiguous, renders the life of the mind tolerable.”[12] I submit that Jaurès—like Rousseau, Robespierre, and Blanqui before him—conceived of politics in cosmic or even metaphysical terms. This is evident when we read the debates between Jaurès and Paul Lafargue concerning Idealism and Materialism in the Concept of History.

Jaurès explained historical materialism dialectically, emphasizing humanity’s evolution from unknowing submission to economic forces toward a future of conscious self-determination. He argued that humanity has been “driven this far, so to speak, by the unconscious force of history,” where individuals do not control their actions but are instead shaped by “economic evolution.” People mistakenly believe they are the agents of historical change or even imagine themselves as unchanging, but in reality, “economic transformations operate on their own terms, and on their own terms operate on men.” Humanity has been “a sleeping passenger carried on by the course of a river,” occasionally waking to notice changes in the landscape, but largely unaware of its own direction.

Jaurès envisioned the socialist revolution as the end of this slumber. In this new era, humanity, no longer driven by “the blind force of events,” will instead “regulate the course of things,” awakening and taking control. However, this “coming era of full consciousness” is portrayed as the result of and dependent upon the “long period of unconsciousness and obscurity” that preceded it. All the ignorant movement of history is revealed to be the preparation for the conscious life of liberated humankind. Jaurès then raised the possibility of taking historical materialist analysis even further by reconciling it with “historical and moral idealism”.

We can see how this grounding philosophical difference cashed out in political practice by turning again to Trotsky:

During the Dreyfus Case, Jaurès said to himself: “Whoever does not seize the executioner’s hand poised over his victim will himself become the executioner’s accomplice” and without pondering the political outcome of the campaign he threw himself into the flood of Dreyfusism. His teacher, friend and subsequent irreconcilable antagonist, Guesde told him: “Jaurès, I like you because your deed always follows on your thought!”

Herein lies the strength and the weakness of Jaurès.[13]

Trotsky’s analysis overlapped with that of Jaurès, for example in opposing terrorist “propaganda of the deed”. However, Trotsky’s sweeping rejection of the “eunuchs and pharisees of morality” along with their “solemn declarations about the ‘absolute value’ of human life” mark a major moral division between the two revolutionaries’ politics.[14] Jaurès put his belief in the absolute value of human life very plainly:

But if socialism and the fatherland are in fact inseparable today, it is clear that in socialist thought, the fatherland is not an absolute. It is not the goal; it is not the supreme end. It is a means to freedom and justice. The goal is the emancipation of all human individuals. The end is the individual. When hotheads or charlatans cry out: “The fatherland above all else!”, we agree with them if they mean that it should be above all our private interests, all our laziness, all our egotism. But if they mean that it’s above human rights, above the human person, we say: No. No, it’s not. No, it is not above discussion. It is not above conscience. It is not above man. […] For socialists, the value of every institution is relative to the human individual.[15]

Jaurès’ politics clashed with both the arid orthodoxies of Marxist-Leninism and the tepid revisionism of postwar social democracy. Jaurès was made a monument to the movement of his time and his political distinctives were politely overlooked.

Another Communism

We can see in Jaurès working out a higher synthesis of historical materialism and moral idealism a similar process to the one Walter Benjamin would elaborate: a reading of Marx too broad-minded to be “Marxist” in the sense that Marx himself rejected—a rejection, that is, of the “peculiar product” of Lafargue and Guesde.[16] As Benjamin put it:

History is the subject of a structure whose site is not homogenous, empty time, but time filled by the presence of the now. Thus, to Robespierre ancient Rome was a past charged with the time of the now which he blasted out of the continuum of history. […] The same leap in the open air of history is the dialectical one, which is how Marx understood the revolution […] Thus he establishes a conception of the present as the ‘time of the now’ which is shot through with chips of Messianic time.[17]

The history of revolutionary movement is not merely one of recording facts and figures. By our collective work, we can redeem the past. Jaurès perceived that pushing republican values to their fullest extent would overthrow the bourgeois order. In this analysis of the real movement, Jaurès saw himself as faithfully carrying on Marx’s work:

Not only does [Marx] announce communist society as the necessary consequence of the capitalist order, but he also shows that it will finally put an end to the class antagonism that exhausts mankind: he also shows that for the first time, full and free life will be realized by man, that workers will have both the nervous finesse of the laborer and the tranquil vigor of the peasant, and that mankind will arise, ennobled and joyful, on the renewed Earth.

Is this not an admission that the word justice has a meaning, even in the materialist conception of history, and isn’t the reconciliation I’m proposing to you, therefore, acceptable to you?[18]

With the defeat of both Marxism-Leninism and social democracy at the end of the 20th century, the international left entered a period of reflection and recomposition. Today, the France Unbowed carry on the Jaurèsian tradition of the radical left: a popular and revolutionary movement, willing to fight here and now for the social Republic against the forces of reaction and the status quo. The Unbowed compose a force that works within the society of today in the service of the society of tomorrow—a radical left that neither dismisses reforms like the ultra-left nor contents itself with crumbs like the center-left.

When Unbowed deputy Antoine Léaument stood up in the National Assembly to defend Communist deputy Soumya Bourouaha, he spoke of history in terms that Jaurès and Benjamin would understand:

Never since I have been an elected representative have I thought that one of my colleagues would be booed for saying that she is the daughter of immigrants. Madame Le Pen, you say you want to expel those who represent a menace to the Republic, but that menace to the Republic is you!

Applause from the left, the right howls.

You menace the Republic when you menace her people, forgetting that 20 million of our compatriots have at least one immigrant parent, grandparent, or great-grandparent. How many of us here, even in this very assembly, have a parent, grandparent, or great-grandparent who was Belgian, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, Moroccan, Algerian, Malian, or German? Raise your hands!

The orator lifts up his hand, as do many others. The right cries “So do we!”

Behold the history of France, Madame Le Pen! You deny it when you target foreigners, because those of us who raise our hands—we do not know if our great-grandparents, grandparents, and parents arrived legally on the territory of the French Republic.

The right shouts, and the orator continues over their voices.

We do not know that history, but we do know that France in all its grandeur is built by and with immigrants, Madame Le Pen!

The left applauds. The orator raises his arm towards the right.

We also know that before us is the face of the old France, that of Vichy, that which never stops inflaming xenophobia—

The right clamors.

—and beside us is the new France, that which stands tall, proud of her republican and revolutionary history, affirming: “Freedom, Equality, Fraternity!”

As he says the motto, the left joins him and rises to their feet in applause.[19]

As he said these words, the great Jaurès spoke through him—and not only his spirit, but the proletariat, the real movement, the Humanity of the future raised their voices. So far from the charges of “social chauvinism” or “liberal universalism” is this politics that those who lob them seem miniscule. Have they forgotten that the final cause of communist politics is the freedom of all? I have seen with my own eyes the weary faces of the oppressed break into a smile when they see the sons and daughters of Jaurès arrive. I have seen the kiss of fraternity break—even if only for a moment—the chains of this age. And with Jaurès, I look for the life of the world to come.

Anatole France, “Letter From Anatole France on the Death of Jaurès”, l’Humanité, 1914. ↩︎

Amadeo Bordiga, “In the Red Light of Sacrifice”, Il Soviet, II/6, 1919. ↩︎

Leon Trotsky, “Jean Jaurès”, Kievskaya Mysl n° 191, ed. 1917. ↩︎

Léon Blum, “Jean Jaurès”, Germinal series 13 vol. n° 12, 1947. ↩︎

Grigory Zinoviev, “A la mémoire de Jaurès”, Bulletin communiste n° 1, 1920. ↩︎

Germaine Berton, “Procès en cour d’Assises”, 1923. ↩︎

Jean Jaurès, “L’émancipation sociale des travailleurs”, Assemblé nationale, 1893. ↩︎

Vladmir Lenin, “Notes of a Publicist”, 1910. ↩︎

Elisa Marcobelli, “La posterité de Jaurès en Italie et Allemagne”, 2023. ↩︎

Leon Trotsky, “Rapport au IV° congrès mondial de l’Internationale communiste”, 1922. ↩︎

Leon Trotsky, “Jean Jaurès”, Kievskaya Mysl n°191, ed. 1917. ↩︎

Henri Guillemin, L’arrière-pensée de Jaurès, 1966. ↩︎

Leon Trotsky, “Jean Jaurès”, Kievskaya Mysl n° 9, 1909. ↩︎

Leon Trotsky, “Why Marxists Oppose Individual Terrorism”, Der Kampf, 1911. ↩︎

Jean Jaurès, “Socialisme et liberté”, La Revue de Paris, 1898. ↩︎

Friedrich Engels, “Letter to Eduard Bernstein”, 2-3 Nov. 1882 ↩︎

Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History”, 1942. ↩︎

Jean Jaurès, “Idéalisme et matérialisme dans la conception de l’histoire”, 1894. ↩︎

Antoine Léaument, “Compte rendu de la deuxième séance du jeudi 31 octobre 2024”, Assemblé nationale, 2024. ↩︎