After the fall of Occupy, a newfound friend from the park handed me a copy of Marshall Berman's Adventures in Marxism. I tore through the book, and it impressed on me the image of communism as the realization of humanism: of “Marx's vision of individual freedom and his program for extending its scope.”[1] Berman was a warm, avuncular writer whose words were effortlessly convincing. Bruno Leipold's Citizen Marx is the first book on the subject that has resonated with me in the same way, and I encourage everyone to read it.

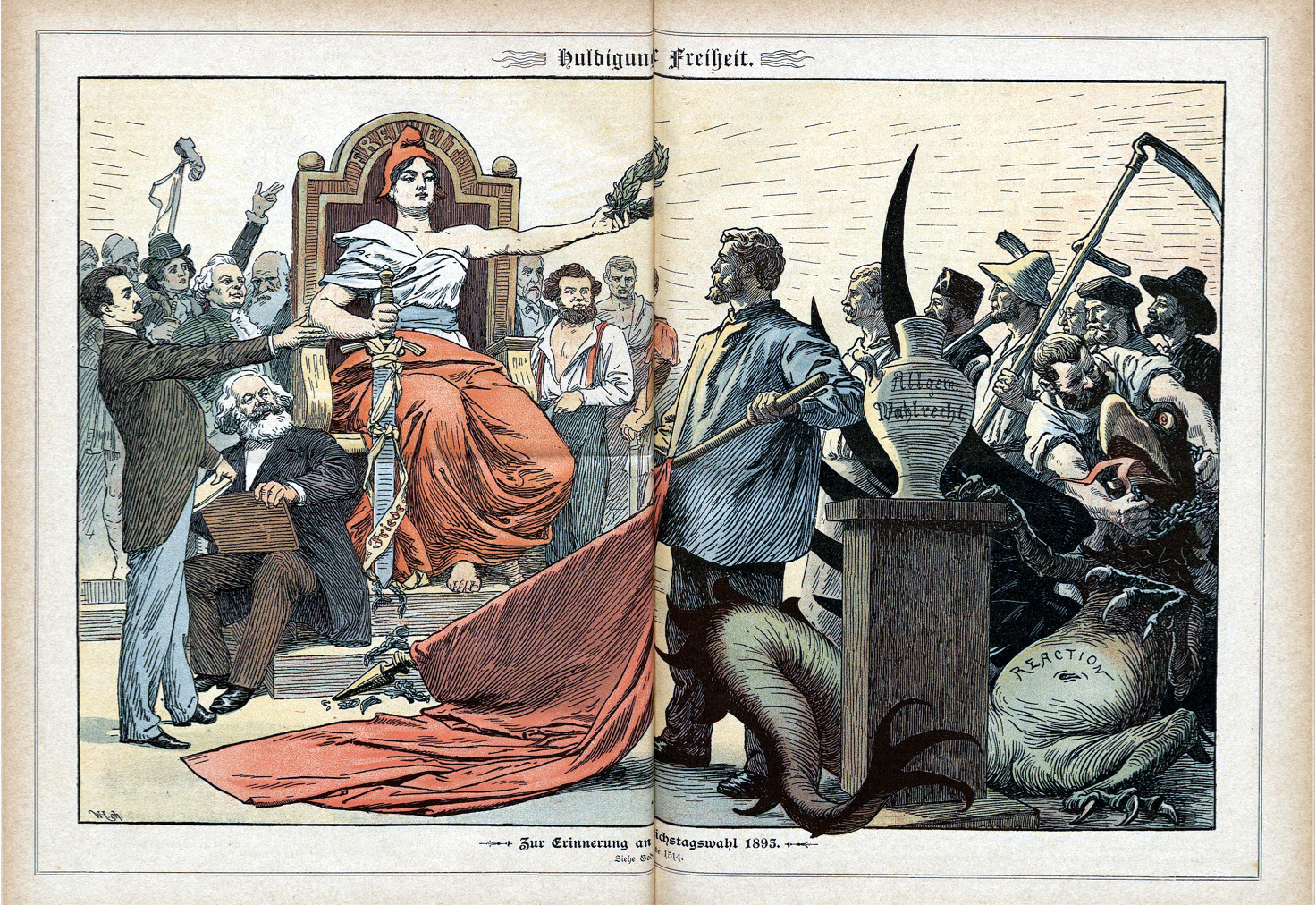

This work has a strong, clear thesis: Karl Marx was deeply influenced by 19th century republicanism and we should study his works in that context because, in Leipold's words, “his republican commitments are still central to the political and social struggles of our day.” My reading this year has snaked through Robespierre, Blanqui, Jaurès, and Mélenchon—and I must say that Leipold's work found its way to me at the most opportune time. Citizen Marx is, perhaps inadvertently, the best English-language introduction to the Marxist inheritance of the contemporary French radical left.

Leipold is a historian and his book methodically advances through Marx’s life and times. We begin with Karl’s student essays on antiquity and end with his mature reflections on the Paris Commune, stopping here and there to examine his contemporaries and their influence on him. I confess that I am generally disinterested in German history and philosophy, and I was still able to follow the author's tour of the intellectual and political context without difficulty. At 440 pages, Leipold's treatment is comprehensive without becoming exhaustingly exhaustive. Consider the coda of the first chapter:

Marx’s early journalism was defined by the tortuous task of continuously pushing for progressive political reform without provoking the Prussian government into outright suppression of the Rheinische Zeitung through overt radicalism. Within those parameters, he defended a free press and the rule of law, and condemned the arbitrary power of censors, forest-owners, and feudal legislators, while only covertly hinting at more radical ideas on representation and the expansive political role he wanted citizens to play in the state. Underlying Marx’s critiques of arbitrary power was his central commitment to freedom. His republican conception of freedom (which has not been sufficiently appreciated) required not only the rule of law, but that laws be democratically made by the people. That view subtly distinguished him from the nondemocratic view of liberty defended by contemporary liberals. Yet Marx still insisted on the need for a broad front with liberals in order to more effectively challenge Prussian absolutism, and he consequently opposed the ultraradical provocations of the Left Hegelian Freien. Balancing such conflicting pressures, while doing his utmost to push against the limits of political and social transformation, was, as we will see, a recurrent feature of Marx’s political life.

Even without reading the preceding pages that elaborate and note all the details, this excerpt evidences Leipold's clarity.

It's frankly refreshing to read Marx within this historicist frame, to see him removed from the clutches of ideologues and presented by such an amiable scholar attentive both to Karl's era and ours. I mentioned above the contemporary French radical left, and it is precisely the exposition of the “universal and social republic” that so endears me to this text. When Leipold cites the lines of William Morris or the last words of the Communards, he is not merely indexing the archives—he is drawing from the depths of revolutionary hope. The haunting lines of Jean-Jacques’ three-note air, Que le jour me dure, recurred to me as I turned these pages.

Now as I have made plain my admiration, I will remark that I would have liked—or would like to see in the future—more discussion of figures and events absent or mentioned in passing. While Paul Lafargue and Jules Guesde are cited in the postface, neither Lafargue's Idealism and Materialism in the Concept of History nor Guesde’s The Two Methods are treated. Both debates with Jean Jaurès reflect differing interpretations of Marx and republicanism. Rosa Luxemburg and Toussaint Louverture likewise have more to say, but Leipold has, in fairness, furnished the basis for further analysis beyond Marx’s immediate environs.

The historic failure of social democracy and stymied attempts at democratic socialism in the new millennium demand more than simply trotting out the faded formulations and moth-eaten orthodoxies of the past. Bruno Leipold has done a service not only to his fellow-scholars, but to all friends of freedom in this new work. Citizen Marx will, I suspect, be a classic reference for the years of struggle to come. As Leipold puts it, “Marx’s critique reminds us that socialists have a legacy of freedom waiting to be reclaimed.”

Marshall Berman, Freedom and Fetishism, 1963. ↩︎